Understanding India’s Import Policy in the Pre-Reform Era

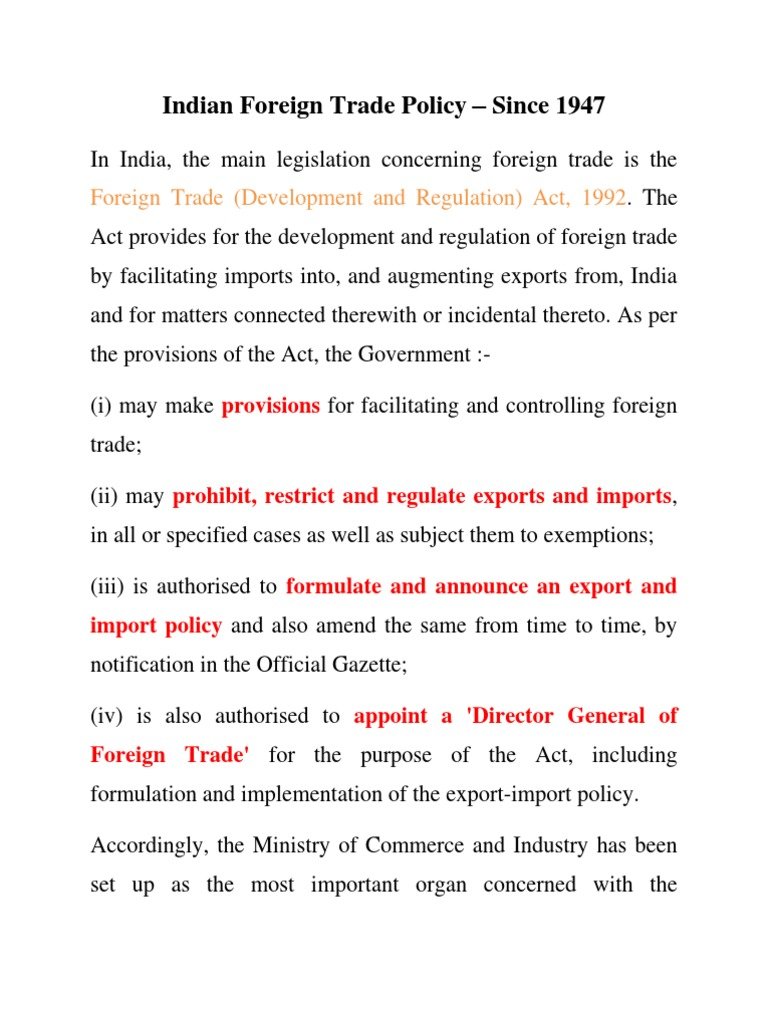

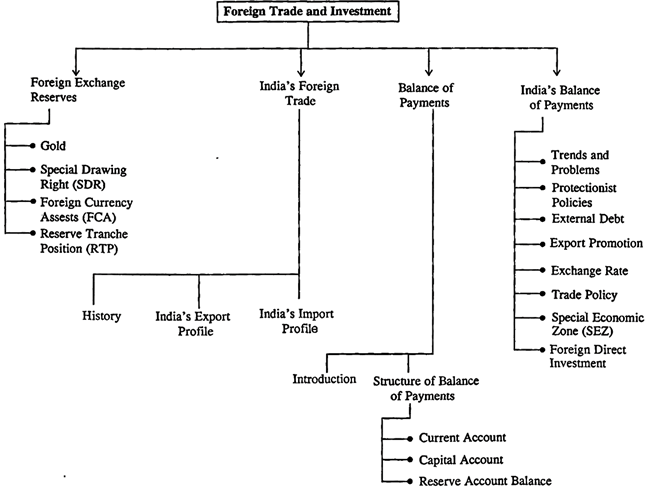

The import policy of the Government of India in the pre-reform period had two important constituents: (1.) Import restrictions and (2.) Import substitution. It was formulated keeping in view the limited foreign exchange reserves of the country, shortages of essential consumer goods in the economy, requirements of capital goods, machinery, spare parts and components for the building up of heavy, basic industries, and the role and scope of import substitution in the country. The period of 1980s was characterized by massive import liberalisation –the desire being to enhance the export competitiveness of large sections of Indian industry.

In the annals of India’s economic history, the pre-reform period stands as a significant chapter, marked by a distinctive import policy that shaped the nation’s trade dynamics. This era, spanning from Independence in 1947 to the early 1990s, witnessed a unique approach to imports that reflected the nation’s socio-economic goals and global positioning.

Table of Contents

A Protective Shield: The Licensing Raj

At the outset, India embraced a protectionist stance, weaving a complex web of licensing regulations known as the ‘License Raj.’ The aim was to shield domestic industries from foreign competition and foster self-reliance. Every import required a license, turning the process into a bureaucratic labyrinth. While the intention was to nurture indigenous businesses, the unintended consequences included stifling innovation and efficiency.

The Quota System: A Controlled Flow

Under the import policy of the time, a quota system was instituted to manage the inflow of goods. Quantitative restrictions were imposed on various items, limiting the quantity that could be imported. This approach, though intended to control the trade balance, often led to inefficiencies and black market activities, as demand often exceeded the permitted quotas.

A Currency Conundrum: The Role of Exchange Rates

Exchange rates played a pivotal role in the pre-reform import policy. The fixed exchange rate system pegged the Indian Rupee to a basket of currencies, attempting to stabilize international transactions. However, this fixed system also meant that India couldn’t adjust its currency to reflect economic realities, leading to imbalances and trade deficits.

Public Sector Dominance: The Maharaja of Imports

The public sector played a dominant role in the import scenario during this period. Large public enterprises controlled the import and distribution of key commodities. While this centralized control aimed to ensure equitable distribution and prevent hoarding, it often resulted in inefficiencies, shortages, and a lack of market-driven competitiveness.

Import Substitution: A Double-Edged Sword

Import substitution was a key tenet of India’s economic strategy during this era. The idea was to replace imported goods with domestically produced ones, fostering self-sufficiency. However, the flip side was a lack of exposure to international best practices and a slower pace of technological advancement.

Impact on Consumers: Choices and Constraints

For consumers, the pre-reform import policy meant limited choices. The scarcity of imported goods resulted in a constrained market, where options were often dictated by government decisions rather than consumer preferences. This scenario gave rise to a culture of ‘waiting lists’ and ‘rationing,’ reflecting the tight control exercised over the availability of goods.

Winds of Change: The Shift Towards Liberalization

As the 1980s unfolded, the drawbacks of the existing import policy became increasingly apparent. India’s economic growth was hindered by inefficiencies, lack of competitiveness, and a stifling bureaucracy. The winds of change began to blow, and the early 1990s saw a paradigm shift with the introduction of economic reform.

Import Restrictions

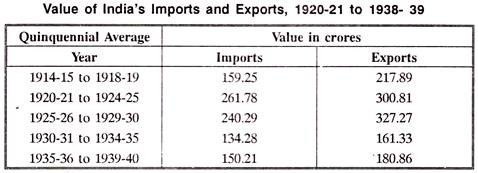

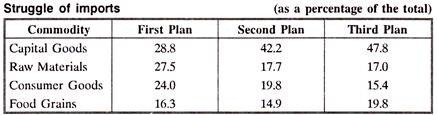

The Mahalanobis strategy of development encouraging large-scale industrialization of the country was initiated in the Second Five Year Plan (which started in 1956-57). Under this strategy of development, the government had to import capital equipment, machinery, components, spare-part, industrial raw materials, intermediate goods, technical know-how etc. in large quantities and this led to a substantial increase in foreign exchange expenditure.

The government also had to resort to import of foodgrains from time-to-time to overcome the shortage of foodgrains. As against this, the export earnings continued to be stagnant. Thus, the government had no option but to severely curtail import expenditure. Therefore, the history of severe import restrictions in the country starts from the year 1956-57.

An import licence allowed a specified amount of a specified item to be imported by a specified user for a specified purpose sometimes even from a specified source of supply.

Import Substitution:

The two broad objectives of the programme of import substitution in India were: (a) to save scarce foreign exchange for the import of more important goods, and (b) to achieve self-reliance in the production of as many goods as possible.

The policy in India has gone through various phases. Broadly speaking, we can discern three distinct phases: (1.) In the earlier phase, import substitution mostly took the form of domestic production of consumer goods; (2.) In the second phase, emphasis shifted to the replacement of the import of capital goods; (3.) In the third phase emphasis was on reducing the dependence on imported technology by developing and encouraging the use of indigenous techniques.

Import Liberalisation in 1980s:

The import policy of the Government of India till 1977-78 varied in degrees of restrictiveness during different plans. It was rather light during the First Plan, intensely sever during the Second, somewhat less so during the Third ( except in the last two years); and perhaps equally so since then (right up to 19977-78).

The year 1977-78 initiated a new era of import liberalisation in the country. This process was carried forward in 1980s.

Policy for Import of Capital Goods:

Since capital equipment is the basic requirement of the industrial sector, the approach in the three-year export -import policies was on providing easy access to imported capital items by progressively delinking them from licensing formalities. A large number of capital goods were placed under OGL (Open General Licence) category, i.e., they could be imported without any import licence.

Policy for Import of Raw Materials:

As in the case of capital goods, a large number of raw materials, components and consumables were placed under OGL in order to enable the actual users (industrial) to procure them without going through the licensing formalities.

Policy for Import of Raw Materials: Import Policy for Registered Exporters:

Because of the dire need for increasing the export earnings of the country, import policies in 1980s were given an ‘export orientation’. The aim of these policies was to provide the Registered Exporters an assured, continuous and uninterrupted supply of the required production inputs, essential for expanding the exports on a sustaining basis.

Policy for Import of Raw Materials: Import Policy for Registered Exporters:

Because of the dire need for increasing the export earnings of the country, import policies in 1980s were given an ‘export orientation’. The aim of these policies was to provide the Registered Exporters an assured, continuous and uninterrupted supply of the required production inputs, essential for expanding the exports on a sustaining basis.

Policy for Export/Trading Houses:

Exporters who fulfilled certain minimum export requirements for a specified period of time were granted the status of Export Houses, Trading Houses, Star Trading Houses or Superstar Trading Houses.

Policy for Import of Technology:

The government allowed liberal import of technology with a view to making export production of the country internationally competitive and also to help in the county’s technological advancement.

A Critical Evaluation of Import Policy:

In this sub section, we present a critical evaluation of the import control regime, the policy of import substitution and the policy of import liberalisation of the pre-reform period

The Import Control Regime:

According to Jagdish Bhagwati and Padma Desai, import policy had the following adverse economic effects: (1.) Delays; (2.) Administrative and other expenses; (3.) Inflexibility; (4.) Lack of co-ordination among different agencies; (5.) Absence of competition; (6.) Bias towards creation of capacity despite under utilisation ; (7.) Anticipatory and automatic protection afforded to industries regardless of costs; (8.) Discrimination against exports; and (9.) Loss of revenue.

The Policy of Import Substitution:

The policy of import substitution enabled the country to achieve diversification and depth so necessary for further growth. However, many economists have argued that the indiscriminate extention of import substitution to a wide range of sectors in India without regard to costs, was not the ‘best’, or the ‘most efficient ‘ policy.

The Policy of Import Liberalisation:

The policy of import liberalisation pursued with a vigour in the 1980s resulted in a substantial increase in the volume of imports. For instance, the volume index of imports was 224.2 in 1988-89 ( base 1978-79 = 100), i.e., in a period of a decade, it had more than doubled.

Conclusion: Lessons from the Past

Reflecting on India’s import policy in the pre-reform period provides valuable insights into the complexities of balancing protectionism and economic growth. While the intentions were noble, the unintended consequences shaped an era marked by bureaucratic hurdles, inefficiencies, and limited global exposure.

As we navigate the complexities of contemporary economic policies, understanding the lessons from the past becomes crucial. India’s journey from a tightly regulated import regime to a more open and globally integrated economy is a testament to the need for adaptability and pragmatism in the face of evolving economic landscapes.